The Still Open Case of Irving Petlin

Kent Fine Art, 210 Eleventh Avenue, 2nd Floor

November 8 – December 20, 2014

A figure raises tall against a brilliant, yellow faceted landscape, his face mask-like, his staff navigating a journey. Through what? The River Styx or Elysian fields – both goodness and violence are intimated. Youthful shapes surface – immaterial – their bodies pixelated in partial comprehension as to their fate as if they – the source of the flowing river – were granted a half-life, the realm of memory that is the role of the painter to prevent from dissolving into oblivion. Entitled “Revolution Pastoral” (1978-1981), this large-scale, double canvas was painted after the end of the Vietnam War when the artist turned from protest to reflecting on the nature of what had transpired, imagining alternate destinies.

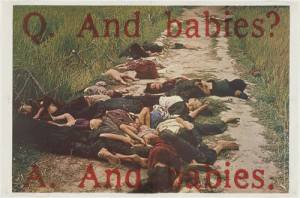

How do you approach the canvas when you accept responsibility for the problems of the world? For Irving Petlin (b. 1934, Chicago) it means visualizing beyond what we are willing to see. As a young, ardent activist during the Vietnam War he connected accountability to atrocity with the question: “And babies?” when he and fellow Art Workers Coalition members Jon Hendricks and Frazer Dougherty created a poster placing a quote from a Mike Wallace CBS News interview over an image by war correspondent Ronald L. Haeberle showing children from the My Lai massacre slaughtered along a dirt path. They unfurled the poster accusationally with its definitive answer – “And babies.” – in front of Picasso’s Guernica at the Museum of Modern Art in an act of institutional intervention and political defiance in December 1969.

After a decade of activism, Petlin turned to large-scale painting as a means to chronicle history. In contradistinction to the immediacy of Abstract Expressionism, narrative painting takes time, patience, and persistence. It is valued more for insistence than urgency; but, in his belief that art can sustain before our sight those events whose slippage from history would be as shameful as the cruelty perpetrated in the name of “just cause,” Petlin ascertains the viability of painting as historical record and critical vision. The strength of truly effective art is not its atemporality but its extemporality: the demand to awaken across and throughout time, acknowledging the past as present before our eyes today.

Two sheets of lightly gridded craft paper, framed and hung side-by-side in the same alliance as the artist’s large, double canvases, reveal a frieze of figures whose solidity is lost in a haze of smoke, their forms enfolded together in a ghost-like mass, the individual distinction of posture and profile dissipated in a chaotic rush of confusion and fear. One lone gunman stands in profile to the far left reminiscent of the soldier executioners in Goya’s The Third of May 1808 or Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian. Through nine windows shines the blood red of sunset. In this preparatory, pastel sketch for Hebron (1997), Petlin uses his preferred medium, in a language that is both sparse and emphatic, to set out his response to the Cave of the Patriarchs Massacre that took place in a Palestinian mosque on February 25, 1994. Still painting today at the age of 80, Petlin continues to share both personal vision and collective history, leaving us to account for our own participation.

[“All That Is Marvelous” represents a turn in Shifting Connections – frequent shorts of 100-500 words on books, exhibitions, and artworks that radiate Eros even as they face the darkest Thanatos of contemporary systems. For more detail see the About page.]