Yevgeniy Fiks, Has anyone ever wondered?, 2014, in “The Lenin Museum” at The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY. Photo: Julia Sherman.

The Lenin Museum

November 20, 2014 – January 17, 2015

The James Gallery, CUNY Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Avenue, New York

Monument to Cold War Victory, October 7 – November 7, 2014

Organized by Yevgeniy Fiks and Stamatina Gregory

41 Cooper Square at Cooper Union, New York

A Gift to Birobidzhan, September 10 – October 19, 2014

21ST.Projects, Critical Practices, Inc., New York

The Wayland Rudd Collection, January 17 – February 15, 2014

Winkleman Gallery, New York

Yevgeniy Fiks, Untitled (The Lenin Museum), 2014; Anatoly, 2014; and Pleshkas of the Revolution, 2013, in “The Lenin Museum” at The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY. Photo: Julia Sherman.

Four exhibitions in a year is rare exposure for an artist in New York City, yet Yevgeniy Fiks (b. 1972 Moscow) has accomplished just that: The Lenin Museum, a solo exhibition exposing the duplicity of expediency and erasure in the instrumentalization of gay culture in Soviet Russia, currently on view at the James Gallery at the CUNY Graduate Center, and three collaborative projects, which confront issues of representation within historical practices of commemoration and identity formation within the public sphere.

The Wayland Rudd Collection at the Winkleman Gallery last spring was a collaborative engagement with the anti-racist representation of African Americans in the Soviet Union and the experience of being a person of color in Russia today. A Gift to Birobidzhan at 21ST.Projects, as part of Critical Practices, resurrected from the archives a failed mission from the 1930s to donate a collection of art to the autonomous Jewish state of Birobidzhan within the Soviet Union. In a return of the historical repressed, the contemporary project also “failed” in its efforts to extend a cultural gift. Finally, Monument to Cold War Victory, organized by Yevgeniy Fiks and Stamatina Gregory, was a conceptual project taking the form of an open-call, international competition for a public, commemorative work of art in recognition of the legacy of Cold War conflict.

When Fiks began his investigations into the Cold War, there was little sense of its relevancy to contemporary society and yet today – a little over a decade since his first artistic production on these themes – hardly a day passes without some reference to freezing East/West relations, the consequences of surveillance here in the US, and the autocratic repression against civil rights and basic human freedoms in Putin’s Russia. “Peoples are not entities,” writes Jean-Luc Nancy. “They are indefinitely exchanged – and changing – signs of our common existence, which itself cannot be gathered under any identifiable ‘humanity’.”[1] Fiks might add that peoples are not (automatic) enemies – for that, they must be constructed as such!

In his work, Fiks consistently emphasizes the dangers of giving into propaganda and its systematic manufacturing of fear, difference, and enemies. He favors the nuanced uncertainty of representational layers in contrast to the reductive quality of icons yet he tactically utilizes one-dimensional card-board cut-outs to underscore the isolation of those individuals set apart as aberrant to society. In unmasking our political and social codes of duplicity, he sets out to unravel systems of exclusion. As a follow-up to Shifting Connection’s first “In sight/In mind” conversation with the artist, Kathleen MacQueen discusses with Fiks the conflation of “spy” with “homosexual” as well as the artist’s application of interventionist tactics to history and social space.

Yevgeniy Fiks, Untitled (The Lenin Museum), 2014, and Untitled (Postcards), 2014, in “The Lenin Museum” at The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY. Photo: Julia Sherman.

Kathleen MacQueen: Yevgeniy, your current exhibition at the James Gallery is titled: The Lenin Museum. In a post-Soviet Russia, Lenin is no longer the cultural icon and political hero he once was. What is the significance of a now defunct institution and a demoted hero as the subject of your exhibition?

Yevgeniy Fiks: I came to this project from two different directions. I have done a lot of projects that have to do with Lenin in some shape or form, whether having to do with his image as a visual representation in official Soviet art or with his writing and what place Lenin’s ideas might have in society today. The other direction is through my research into the gay and lesbian community in the Soviet Union through which I discovered that the Lenin Museum was a gay cruising site during the Soviet era – not only the public bathrooms in the basement of the museum but also a movie theatre on the second or third floor that screened documentary films about Lenin. So there were these two directions: the Lenin direction and the Soviet gay research and the museum became the meeting point.

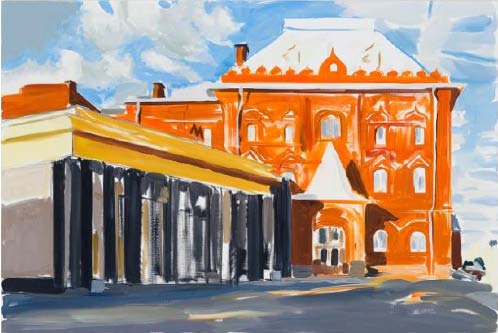

KMQ: O.k., then let’s continue with meeting points: the exhibition prominently features nine paintings of state monuments in Moscow. Let’s talk about “pleshkas” – first of all what are they?

YF: “Pleshka” is argo for gay cruising site and literally it means a bald spot on the top of the head. The term originated sometime during the Soviet era.

KMQ: I can imagine no more excessively public place in Moscow than the state monuments used as cruising sites for gay encounters. Katherine Carl, the exhibition’s curator, talks about the idea of “hiding in plain sight” – how is this safe and is it possible to know if there was any subversive intent in such institutional shadowing?

YF: This appropriation of state monuments for gay cruising sites is, more than likely, coincidental; yet, it is also highly practical because of their convenient location in the city center close to public transportation. You can cover those ten sights in about twenty minutes by foot. And though my paintings do not depict this, it is also a busy public area full of people where it would be difficult to discern what might be unintentional subversive behavior, as you say. It’s important to me that these are “pleshkas” – gay cruising sites of the revolution – a revolution that failed gay and lesbian people. There was decriminalization for the first sixteen years and then in 1934, homosexuality was recriminalized, which endured for sixty years until the Soviet Union collapsed. This revolution that was supposed to bring universal liberation for everyone failed and yet gays appropriated the monuments of the revolution for their cruising sites in spite of the predicament they faced.

KMQ: Was it the revolution that failed or that Stalin failed the revolution?

YF: True, yes.

KMQ: These paintings depict a structure at its utopian best – a sunny, picture postcard emptiness – that prompts a myriad of contradictory associations: cold, Russian winters, the snow, Edward Snowden, secrets, speaking in code, a language of spies, hidden meaning, latency, latent homosexuality, homosexuality expressed in coded language; coming out, coming in from the cold; longing, belonging? How is the figure of the spy related to (or even conflated with) the figure of the homosexual in Cold War history?

YF: It’s a fantastic question. There are a lot of references to homosexuals as spies in the Cold War context. Harry Hay, for example, founder of the American gay and lesbian movement, mentions in his memoir how in the 40s and even 50s people would come into the communist books store in Los Angeles and behave very cautiously, not making eye contact with someone buying books, for example, because maybe this person is working for the government. For Hay, the behavior of the American communist was similar to how the American homosexual would behave at the time…

Yevgeniy Fiks, Untitled (Guy Burgess’s Drawings), 2014, in “The Lenin Museum” at The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, CUNY. Photo: Julia Sherman.

KMQ: …in the sense of hidden intentions?

YF: Yes, it links us to the Cold War. One artwork in the exhibition refers to Guy Burgess, the British spy who fled to the Soviet Union in 1951, one of the Cambridge Five, the ring of upper class Brits who worked for the Soviets. In the exhibition, he becomes the personification of the communist, homosexual spy – the nightmare of Western/Soviet relations.

KMQ: You make use of excerpts from Lenin’s own writings within the exhibition to underscore the theme of latency and homophobia…

YF: I’ve created within the exhibition my own rendition of the Lenin Museum as monument by portraying the museum façade on the doors of two bathroom stalls. Scribbled on the walls of the stalls are statements by Lenin that I found in a book by Nathan Leites, an American sociologist of Russian origin who worked for the Rand Corporation.[2] In 1951, the Rand Corporation published his research in a book titled, The Operational Code of the Politboro, in which he intimates Lenin’s latent homosexual leanings. So the bathroom graffiti are both Lenin quotations and Leites’ conclusions.[3] All of this recycles Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality (1950) – his research into Nazi society – that implicates Nazi brutality with repressed homosexuality, using Freud as a Cold War weapon…

KMQ: …and the conflation of political perversion with a notion of sexual perversion; but this must have had earlier ramifications?

YF: In 1933, a man named Yagoda who was head of NKVD, which was the precursor to the KGB, wrote a memo to Stalin pointing out a link between Soviet army officers, party apparatchiks, and Germany spies – and they were all homosexuals according to him. The fear at that time was Germany so Stalin said, “We have to punish those bastards.” This, in any case, is one story implicating a fear of spying – “a spy in our midst” – with the re-criminalization of homosexuality in 1934. This in turn is very similar to what happened during the McCarthy era in America that I addressed in a previous exhibition at the Winkleman Gallery, Homosexuality Is Stalin’s Atom Bomb to Destroy America.

KMQ: In a review of a subsequent exhibition at Winkleman Gallery this spring, Holland Cotter calls you “a virtuoso in the art of recovering cultural memory.” If we think about the recovery of cultural memory, the implication is that cultural memory exists; however, you point out through your work that so very little memory can exist because it’s been erased. Your work centers on the absence of the gay and lesbian communities from the archive; they’re not in the history. Is your work also a project to expose the systems by which the exclusion takes place?

Monument to Cold War Victory, installation view, including Back to Moscow (Назад в Москву), 2014 by Constantin Boym (b. 1955, Moscow, Russia: lives New York, USA) and Hollywood Ten, 2014 by Szabolcs KissPál (b. 1967, Marosvásárhely, Romania; lives Budapest, Hungary).

YF: My contribution to writing LGBT history is not unique; I see my work as part of a much broader engagement with repressed histories. There are, for example, unofficial archives but even here the gaps are obvious: memories are partial, even painful; people do not wish to talk about it…there are a lot of problems. How to retrieve memory in an ethical manner and in cultural forms that are adequate to that history?

This absence within the Soviet closet – not showing people, showing only places, showing text over images – is a more adequate representation of that history in cultural forms that are organic to Soviet gay and lesbian community: Soviet painting, cityscape, painting in frames are all acceptable forms where the narrative is hidden.

The “pleshkas,” for example, are painted in a very common style – this is Soviet popular painting – constrained and limited. They would be very familiar to a Russian public. There is nothing “gay” in those paintings. And that’s the whole point. Instead of presenting Soviet LGBT as repressed, marginalized, and alienated, I am making a Soviet statement instead.

KMQ: Are you creating in this way an inherent inclusion where the expectation is exclusion?

YF: Yes, I think so. This is popular art, nothing “foreign” about it! You can’t reject it; it’s part of a known visual language within a larger Soviet narrative.

KMQ: Within a larger Soviet narrative, were the pleshka’s known to a wider population?

YF: Some of them, yes, but this does not take away from the fact that many members of society were not even closeted but completely repressed – they could not admit to themselves that they were gay.

Dolsy Smith (c. 1978, New York, lives Washington D.C.) and Kant Smith (b. 1983, Lafayette, LA; lives New York), Clandestine Reading Room, 2014.

KMQ: Is there a difference between the Cold War era and now? Or has Putin’s Russia returned to this rhetoric?

YF: There are two videos in the exhibition that underscore the extreme predicament of representing gay and lesbian history in Russia.

The first is near the entrance. It’s called “Has anyone ever wondered?” and is made as a monument with a pedestal holding red carnations (from a gay-owned flower shop on the Upper East Side), commonly used to commemorate historical occasions. Next to that is a monitor with a one-minute clip from the Russia 1 Channel with Dmitri Kiselyov, a famous TV host who is now head of the Russian Propaganda Agency. The entire show was dedicated to the subject of homosexuality and here he asks in 2012: “Has anyone ever wondered who is bringing flowers to Lenin’s monument? Have you ever thought they must be homosexual because they must be grateful to Lenin for not sending them to the gulag? Etc.”

KMQ: So in one very simply reference to the laying of flowers in commemoration, this TV host discredits Lenin, communism, gays and lesbians?

Dolsy Smith (c. 1978, New York, lives Washington D.C.) and Kant Smith (b. 1983, Lafayette, LA; lives New York), Clandestine Reading Room, 2014

YF: What I see happening in Russia is an increasingly less nuanced rhetoric. In that sense, we might consider this a return to Cold War “clarity” – the simplistic rhetoric of stereotypes. The media is not so different here in the US. For example, the head of the Russian Intelligence Agency was referred to in a recent headline as a spy! Would the US press call the head of the CIA a spy? That’s very clear propaganda.

The other video in the exhibition takes up the story of Anatoly who was the working class boyfriend of the British, communist spy, Guy Burgess. Ironically, the Soviet revolution liberated Anatoly as a gay man only so long as he was in a relation with Guy Burgess because Burgess was known to be gay but was useful to the Soviet system so they closed their eyes. This is a Soviet gay utopia – one individual in a country of 250 million – that’s the extent of liberation!

KMQ: So what’s your intent? What is your tactic with these narrations?

YF: So the story of Anatoly is two lines in the biography of Guy Burgess; he is merely a prop. Can we refocus on Anatoly as a working class electrician? I wanted to animate him into a subject. I was less interested in a historically accurate story as empowering a contemporary LGBT community to tell how they might imagine the story. They speak from experience, some of them of life before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

KMQ: This is what I find so beautiful about the narration is that their own stories are embedded in their fabricated biographies of Anatoly.

YF: [laughter] Yes, very much so.

KMQ: Here you have a multiplicity of layers of official views, social perspectives, and personal identity. For Roland Barthes, it is the singular iconography of the signifier rather than the tonal instability of multiplicity that holds sway over our collective imagination.[4] Your work plays between the cardboard cut-out of simplistic representation and nuanced complexity and multiplicity of voices. Did you set out to confront the limitations of iconicity or did you discover these problems along the way?

YF: Art is precisely the space for raising these kinds of questions. I tend to react only when I see a problem of limitation that stimulates in me an impulse of protest. These tend to be those situations of such conviction in intellectual society where we have already arrived at truth, sorted it out…this feels like too much of a consensus to me, something is wrong.

KMQ: Is your project, then, the tripping up of consensus?

YF: When I notice, then my project activates!

KMQ: Since we last spoke, you’ve added a new methodology to your practice – a collective curatorial engagement – that you first introduced this past spring at Winklemann Gallery in your exhibition, The Wayland Rudd Collection. Then there’ve been two other exhibitions this fall – A Gift to Birobidzhan at 21ST.Projects as part of Critical Practices and Monument to Cold War Victory at Cooper Union – that are also collaborative projects. What prompted this kind of engagement?

YF: A Gift to Birobidzhan is about five years old. I think that is my first collaborative project and The Wayland Rudd Collection was the second. There I had the idea about four years ago and invited others to participate about two years ago. The Anatoly project was also a collaborative project because it grew out of a sequence of meetings rather than out of an idea I had alone.

It makes sense to me to turn something into a participatory project when I feel I cannot handle a project alone. For example, my viewpoint was insufficient for the Wayland Rudd project. For that I needed Afro-American and Afro-Russian perspectives. It comes from an awareness of my own limitations in tackling a project that already is made up of multiple voices. The Wayland Rudd project began as a collection of 200 images made by 100-150 artists! How would I dissect that myself?

Camel Collective, est. 2005 by Anthony Graves (b. 1975 South Bend, IN; lives New York) and Carla Herrera-Prats (b. 1973 Mexico City D.F., lives New York/Mexico City), Cold War Vets Parade, 2014.

KMQ: Are you trying to bring a broader awareness or to complicate our awareness of the post-Cold War legacy?

FY: Complicate, yes… The Cold War Victory Monument exhibition narrates about the compilations of the Cold War as we experience its repercussion and current rejuvenation today. The legacy of the Cold War is not only nostalgia for the 1970-1980s American popular culture but also quite real problems of environmental degradation, growth of inequality, political cynicism, etc. The impact of that conflict goes beyond the level of government sparring.

KMQ: We also find the metaphor of unheimlich – the exile, outsider, or stranger – reflected in your exhibitions this year: with African-American expats in the Soviet imaginary, with homosexuals in the Cold War imaginary, and with the utopian ideals of Jewish Territorialism. What is the possibility of refiguring statelessness and invisibility through these projects?

YF: That is so complex. I would need to think about this but it’s an important question.

KMQ: So let’s approach it from another angle: if we were to extrapolate from Lucy Lippard’s notion of a “multi-centered society” and re-conceptualize this statelessness from “alienated displacement” – what a beautiful term in reference to your work! – to its own kind of migratory aesthetic? In other words, what if we take the hopelessness of statelessness, which is such a desperate condition and so relevant today, and offer it agency through movement, circulation, and alternating stewardship? Can we transfer statelessness to migration with agency?

YF: Hmmm

KMQ: O.k., to take a concrete example – A Gift to Birobidzhan – rather than see it as a project of a cultural exchange that failed to materialize, perhaps it could exist as a roaming collection that transfers stewardship from place to place and think through your use of location as a stand-in for conditions of outsider-ness and exile. Movement as positive opportunity.

Michael Wang (b. 1981, Olney, MD; lives New York) The Mona Lisa Gown, 2013. [A facsimile of a gown worn by the First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy at a state ball immediately after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.]

YF: It’s beautiful.

KMQ: Your idea of participation has drawn me in and inspired me to think in new directions about transfer, even transference, and potential. Here your conceptual practice merges with activism since it elicits engagement…maybe this is not a word you would choose?

YF: Definitely “conceptual” but my work deals largely with historical issues. Even with the Anatoly project, which brought me together with an activist community in Moscow, my forms and my thinking are still conceptual. But we’ll see if I continue with the historical past or connect with the present. At this point, I see my work as interventionist more than activist.

KMQ: As a historical intervention, your work asks us to read between the lines or as Judith Butler intones us to listen or imagine beyond what we are able to hear.[5] In addressing sites of conflict and historical trauma, how do you propose we reclaim restitutive speech in the sense of restitutional justice?

YF: Amazing question! But let’s leave that one to think about!

KMQ: I’m happy to leave this conversation open-ended.

YF: [laughter] Thank you.

Monument to Cold War Victory, installation view including National Cold War Monuments and Environmental Heritage Trail by The National Toxic Land/Labor Conservation Service (est. 2011, United States) and Aerial by Francis Hunger (b. 1976, Dessau, Germany; lives Leipzig, Germany).

[1] Jean-Luc Nancy, Identity: Fragments, Frankness, trans. François Raffoul (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015), 32.

[2] Leites applied principles of psychoanalysis to the study of world leaders and his analysis of foreign relations. See his New York Times obituary from June 10, 1987.

[3] According to Fiks, Leites’ research was allegedly carried out under the auspices of the Harvard Project, an exhaustive research study contracted by the US Air Force from 1950-54. See David Brandenberger, “A Background Guide to Working with the HPSSS Online.”

[4] Roland Barthes, S/Z, An Essay, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Inc., 1974), 41-2.

[5] The quote is: “Our collective responsibility not merely as a nation, but as part of an international community based on a commitment to equality and nonviolent cooperation, requires that we ask how these conditions came about, and endeavor to re-create social and political conditions on more sustaining grounds. This means, in part, hearing beyond what we are able to hear.” Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London and New York: Verso, 2006), 17-18.