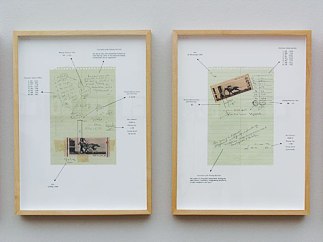

Walid Raad, Letters to the Reader (1864, 1877, 1916, 1923), 2014, installation view showing walls created by Suha Traboulsi, Warsaw Museum of Modern Art. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut.

Who is Suha Traboulsi? Her work has been shown most recently in Here and Elsewhere, the New Museum’s 2014 strident overview of contemporary art from and about the Middle East. It is also on view through this week in a group exhibition, Dissolving Margins, at the Paula Cooper Gallery. She has been written up as a conceptual performance artist but the works on display in both venues are from a set of 27 small abstractions of ink on paper. Ostensibly made in the 1940s, they are more refined and pictorially resolved than one might expect from a young artist in her twenties considering, say, the exploratory investigations of On Kawara’s “Paris-New York Drawings,” created in his early thirties and featured in his retrospective at the Guggenheim. And given the recent fascination for Etel Adnan’s work, one wonders if there isn’t a trend to resurrect, in their swan song years, modernist women artists working in abstraction. In either case, questions arise.

Who is Suha Traboulsi? In regards to any interchange with artists from the Middle East, most of us in the West writing about art would have to begin from a place of “not knowing” as the editors of a 2012 BAK publication on artistic practice admitted in a conversation with actor, director, and artist Rabih Mroué.[1] He agreed that he, too, began his work in a place of “not knowing” – that the complexity of history in any location demands a certain degree of humility. Mroué belongs to a generation of artists who met regularly to share thoughts, experience, and opportunities in coping with and articulating the complexity of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) and its aftermath.[2] The Lebanese writer and artist, Jalal Toufic, is an important mentor and the arts association, Ashkal Alwan, founded in 1993, serves as a platform for interdisciplinary artistic practice in the region and abroad. Walid Raad, though his family fled the conflict and he earned his degrees from the Rochester Institute of Technology (including a PhD in 1996), is part of this generation and group of artists who continue to support each other’s work.

Who is Suha Traboulsi? In Dissolving Margins, she is the only artist in the exhibition not represented by Paula Cooper. It is interesting to imagine that Raad, who is represented by the gallery, perhaps exchanged his own place to give an unknown artist rare exposure, flipping the cards of opportunity to her advantage. In what ways could such a magnanimous act – equivalent to the theatrical model of the understudy – be performed openly within the art world with no strings attached? What would such a substitution constitute in the realm of status, economics, and fair play? How many canonical male artists would transfer their benefits to women (or transgender artists) to achieve parity? Would such a model ever become viable (expanded to include a wide range of invisibilities) in a market and trend driven arts economy?

Who is Suha Traboulsi? The press release confirms her role as an “artist who greatly influenced Walid Raad” (my imaginative speculation not a disconnected fancy) and so to know Suha Traboulsi, one makes a connection to Raad whose fifteen-year project – from 1989 to 2004 – to research and document the contemporary history of Lebanon, particularly the Lebanese Wars of 1975-1991 was performed under the guise of a fictive collective known as the Atlas Group, which consisted of work presented under a number of different identities, including Ingrid Serven and Lamia Hilwé. Shall we add Suha Traboulsi to the list?[3] In 2007, Raad began his second on-going broad archival investigation with installations, individual works, essays, and performance/lectures entitled “Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: A History of Art in the Arab World,” which begins from a radical position of disavowal of the record.

Walid Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: A History of Art in the Arab World, installation view, documenta(13), 9 June – 16 September 2012 in Kassel, Germany. Courtesy the artist and gallery Sfeir-Semler Beirut Hamburg.

How do we write about work in relation to notions of authorship, originality, and precedents or influences? How much of an artist’s practice do we recognize as quotation, parody, or even fiction? How do we shape a history around practices of representation? History, Nietzsche reminds us, is written by the victors (when it is written at all). There are many conditions under which history is lost or obliterated: slavery, revolution, war, genocide, and catastrophe. It is catastrophic in itself to have no history. Do we forget and live in the present? Or do we write fictions? In a 1977 interview, Foucault claims:

I am fully aware that I have never written anything other than fictions. For all that, I would not want to say that they were outside the truth. It seems plausible for me to make fictions work within truth…and in some way to make discourse arouse, “fabricate,” something which does not yet exist, thus to fiction something. One “fictions” history starting from a political reality that renders it true, one “fictions” a politics not yet in existence starting from a historical truth.[4]

The Atlas Group – Walid Raad, Notebook volume 72: Missing Lebanese wars, 1989. Attributed to: Dr. Fadl Fakhouri. © Photo: Walid Raad. Repro: Haupt & Binder.

In a society in which the experience of reality has become hyper-mediated, literature, art, film, music, and performance can be as influential as (and at times indistinguishable from) reality. What of history? When there is no archive (or the internet serves as primary source material), how much do we know to be true and how much do we infer as truth? In The Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (1874), Nietzsche writes that “the capacity to build a new future depends on our ability to see a fundamental continuity with the strengths of the past”– with Modernity, according to Nietzsche, lacking in historical connection.

Jerry Saltz once wrote that Raad’s work was like a “communiqué from a secret agent.”[5] Isn’t it more like a witness protection program fabricating new identities around ones lost to historical disadvantage? Witnesses of an ever-widening breach between history and its erasure in this disavowal of the conditions for participation. In a recent talk, Sigrid Hackenberg y Almansa honors Foucault’s language and his voice, as “[a]n extraordinary accent, elegant, cordial, civil, yet insurrectionary, thus Foucault animates disappearance.”[6] Walid Raad streams in his wake; it’s a turbulent course masked by the veneer of assumed identities. Other artists in the Beirut group – Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, and Akram Zaatari – each in their own way “fictions” history starting from a political reality that renders it true. If representation – like the premise of Paula Cooper’s “Dissolving Margins” – is akin to “an unsettling conspiracy,” it behooves the viewer not so much to uncover and expose the fictions as to wonder what it is we do not know about the facts and why we accept such bold misapprehensions of the conditions of truth.

⊃⊂

Dissolving Margins

with Jonathan Borofsky, Sam Durant, Matias Faldbakken, Emily Feather, Liz Glynn, Robert Grosvenor, Douglas Huebler, Christian Marclay, Justin Matherly, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Rudolf Stingel, Suha Traboulsi, and Kelley Walker

is on view through April 25, 2015 at

Paula Cooper Gallery

521 W 21st Street, New York, NY 10011

⊃⊂

[1] See Maria Hlavajova, Jill Winder, and Cosmin Constinas, “In Place of a Foreword: A Conversation with Rabih Mroué” in Rabih Mroué: A BAK Critical Reader in Artists’ Practice (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, and post editions, 2012), 12-13.

[2] Ibid. 17. Artists in this circle include Mroué’s collaborator and partner, Lina Saneh, along with Tony Chakar, Walid Sadek, Bilal Khbeiz, Walid Raad, Akram Zaatari, and Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige.

[3] Barry Schwabsky writing for The Nation uncovered the relation of Traboulsi to Raad in his review of the New Museum’s 2014 exhibition, Here and Elsewhere. See “Under Pressure: How much of the pressure of reality can a work of art bear before it ceases to be art?” The Nation, October 13, 2014 (online September 28, 2014).

[4] Michel Foucault quoted in Timothy Rayner, “Between fiction and reflection: Foucault and the experience-book” in Continental Philosophy Review 36 (2003): 27-8. In his abstract, Rayner defines an experience-book “as a use of fiction in the practice of critique with desubjectifying effects.” I thank Sigrid Hackenberg y Almansa for reminding me of Foucault’s dissolving of the margins between practice and experience.

[5] Jerry Saltz, “Interrogation Nation: Art that is like a detective report or a communiqué from a secret agent,” The Village Voice, February 7, 2006.

[6] Sigrid Hackenberg y Almansa, “parafoucault parafictions: The White City, December,” unpublished paper presented during the Engaging Foucault conference, organized by the Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, Group for Social Engagement Studies, University of Belgrade, December 5-7, 2014.